NORIAS OF HAMA

Have you ever considered what it takes to get water to your cup? In ancient times, prisoners were tortured on "treadwheels," screaming in agony as they pumped water (de Miranda 112). Yet, in medieval Syria, those screams were replaced by the deep, ominous tones of "the wailer." (loud sound warning).

“Ali, Ali you cry as you turn, O wheel.

Why do you groan, O wheel, where is your pain?

Were you separated from your beloved, or your homeland?

Why do you groan, O wheel, where is your pain?”

(Öztelli qtd. In Alvan 476)

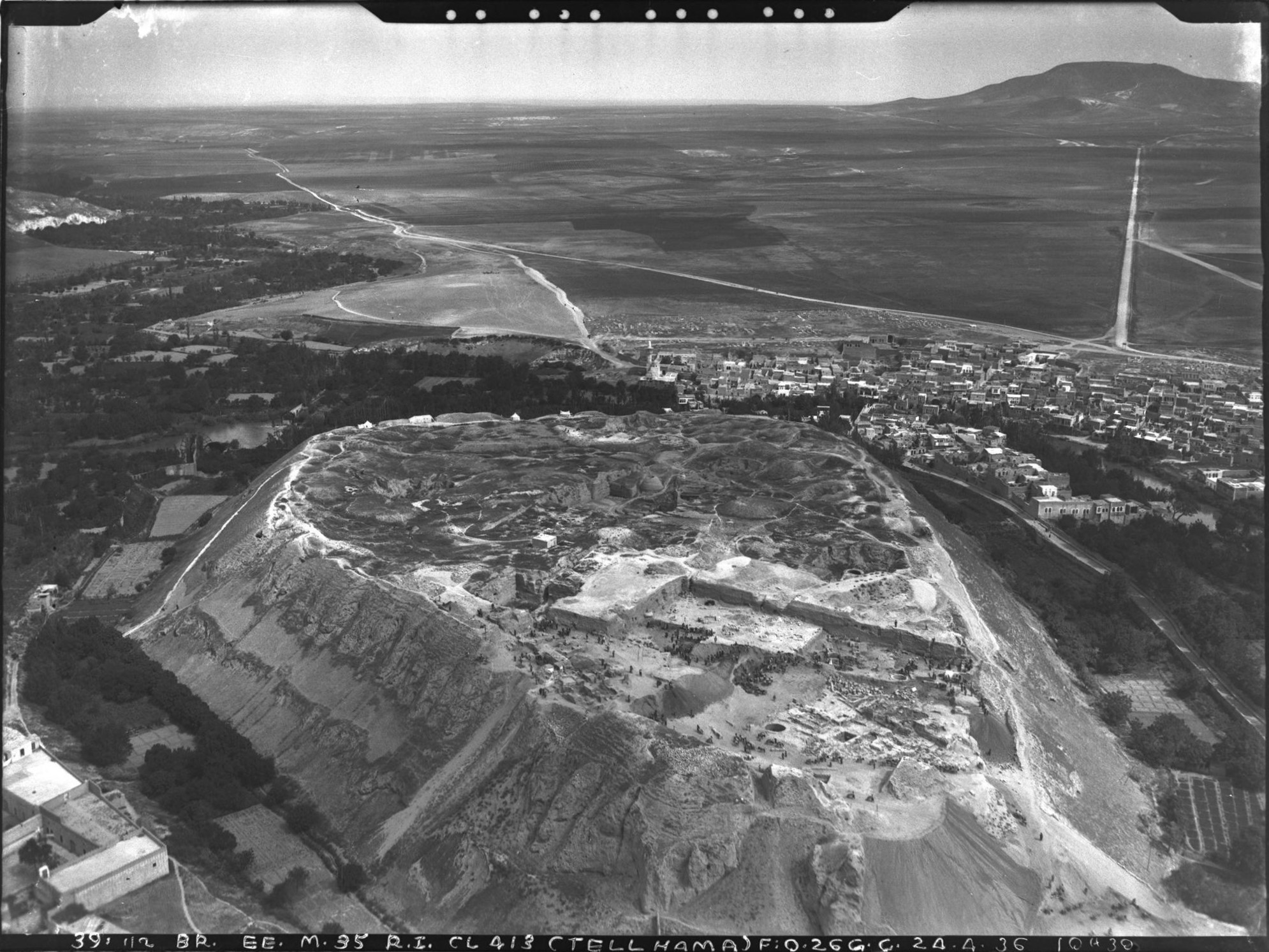

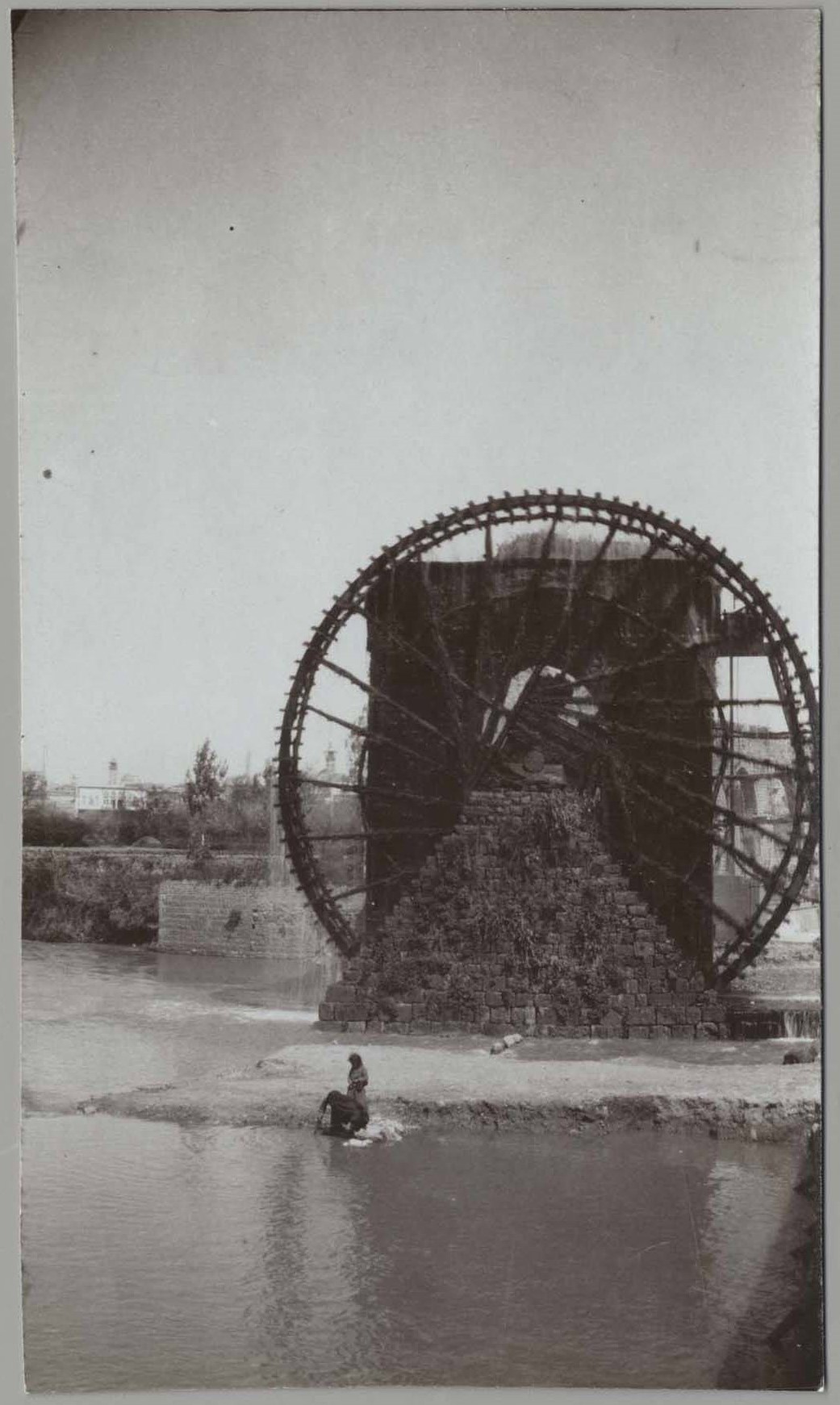

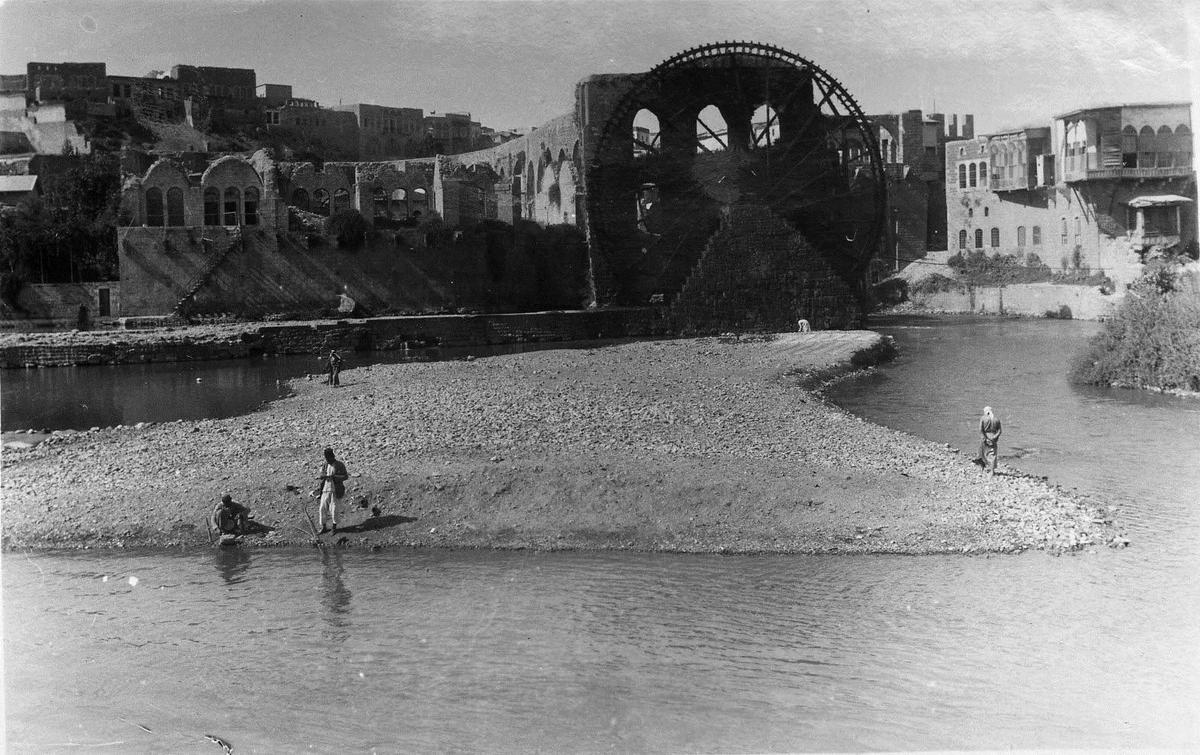

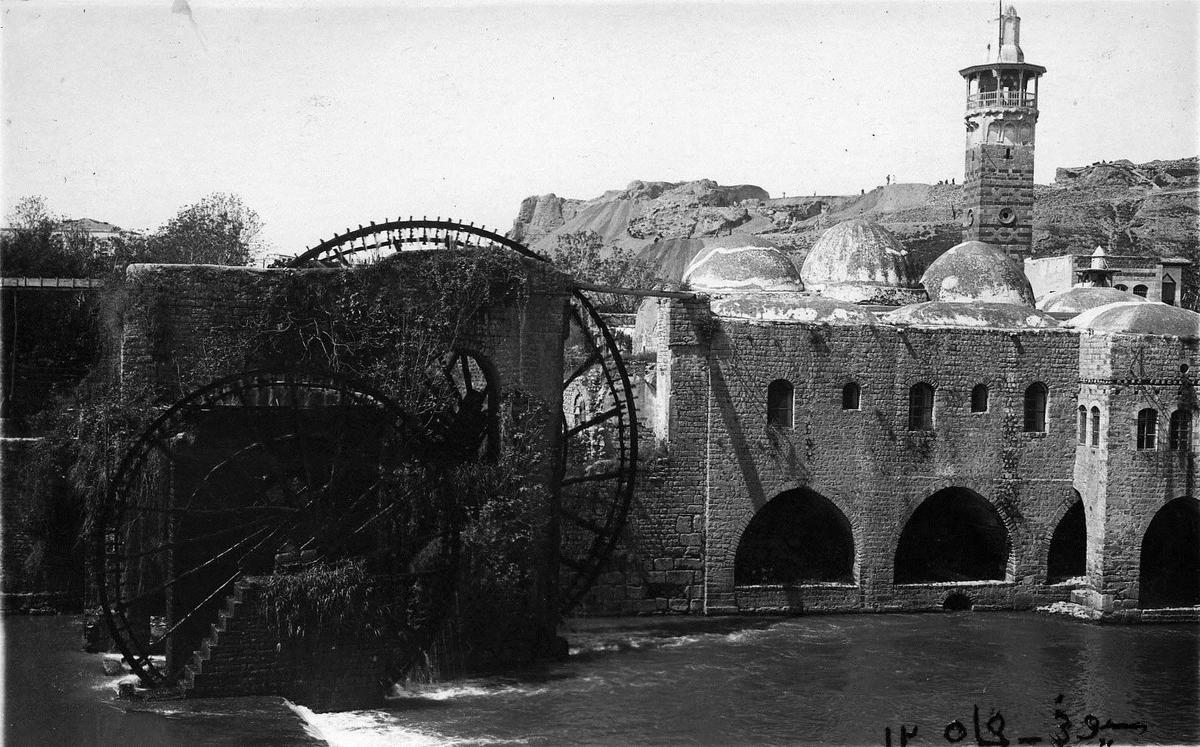

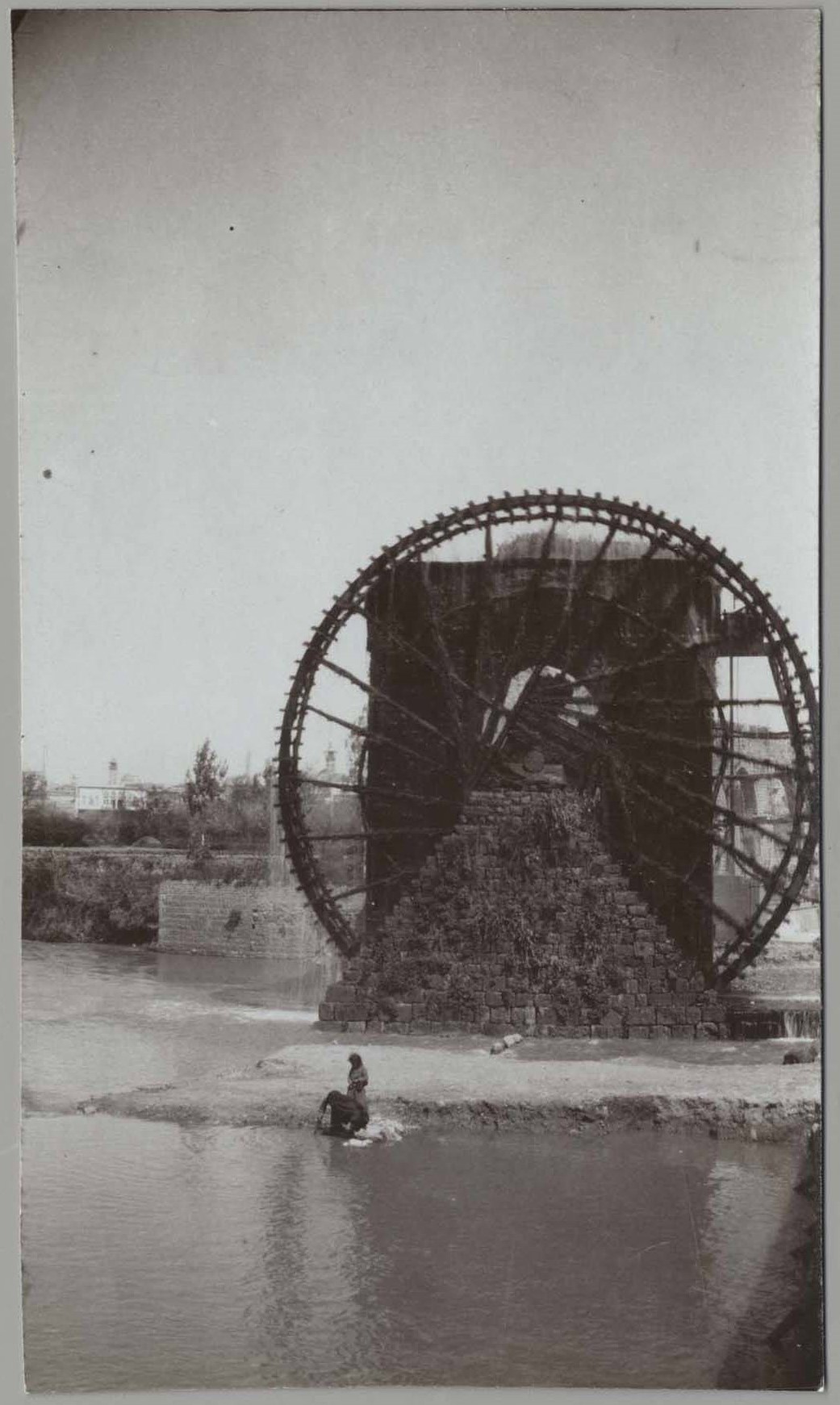

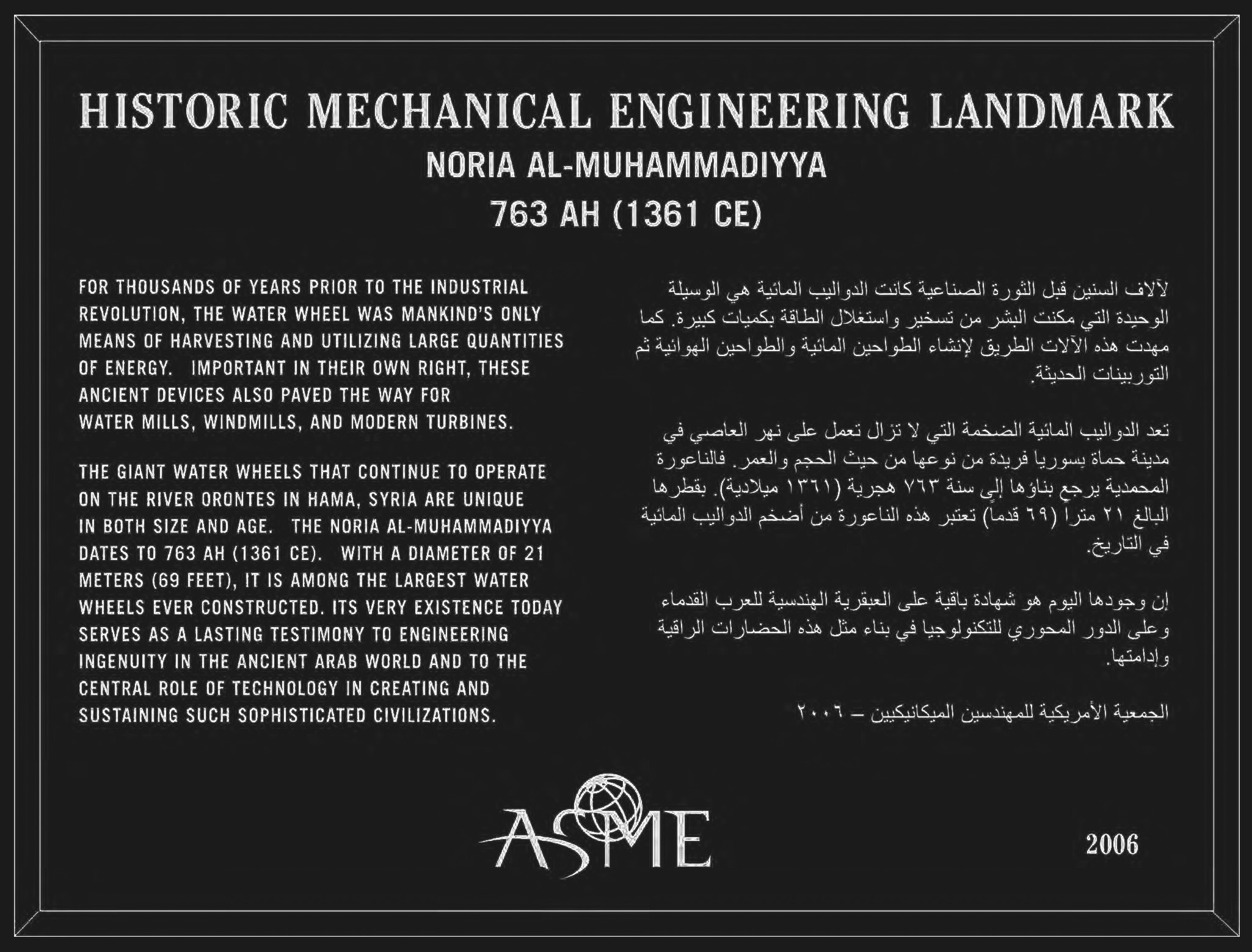

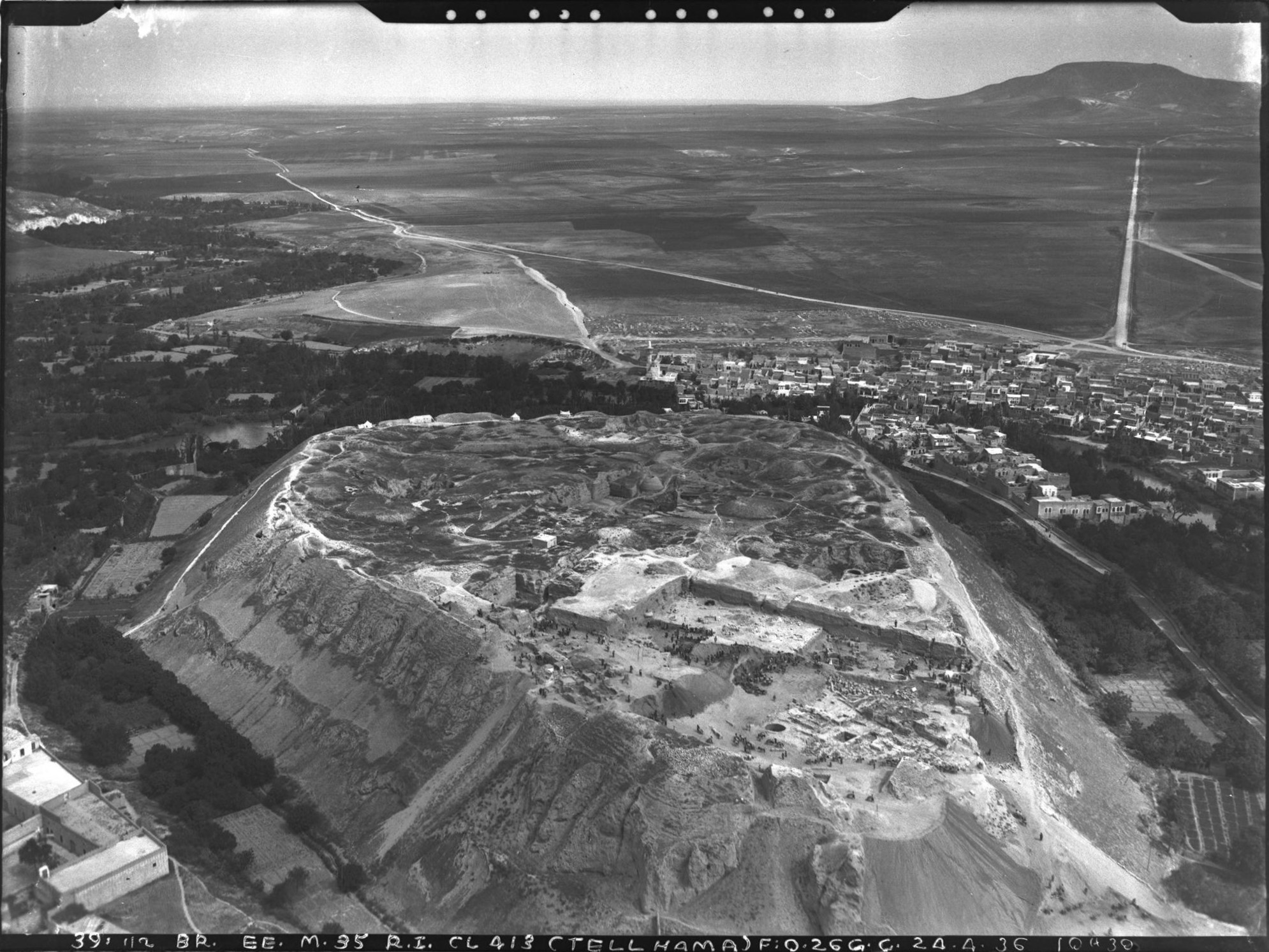

The pain comes from the wood of the wailers, called noria or norias, as they spin on their axles, creaking from the force of the river. These colossal water-lifting devices tower over the Orontes River, with the largest, Noria al-Muhammadiyya, reaching an impressive height of 69 feet (ASME 7). These engineering marvels were instrumental in transforming the declining settlement of Hama into “the city of water wheels,” one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in the world (Astour 51-54; Wilson 1-32). At Hama’s city center lies “the mound,” a prehistoric settlement dating back to 6000 BCE (See Fig. 1.2) (National Museum of Denmark (NMOD)).

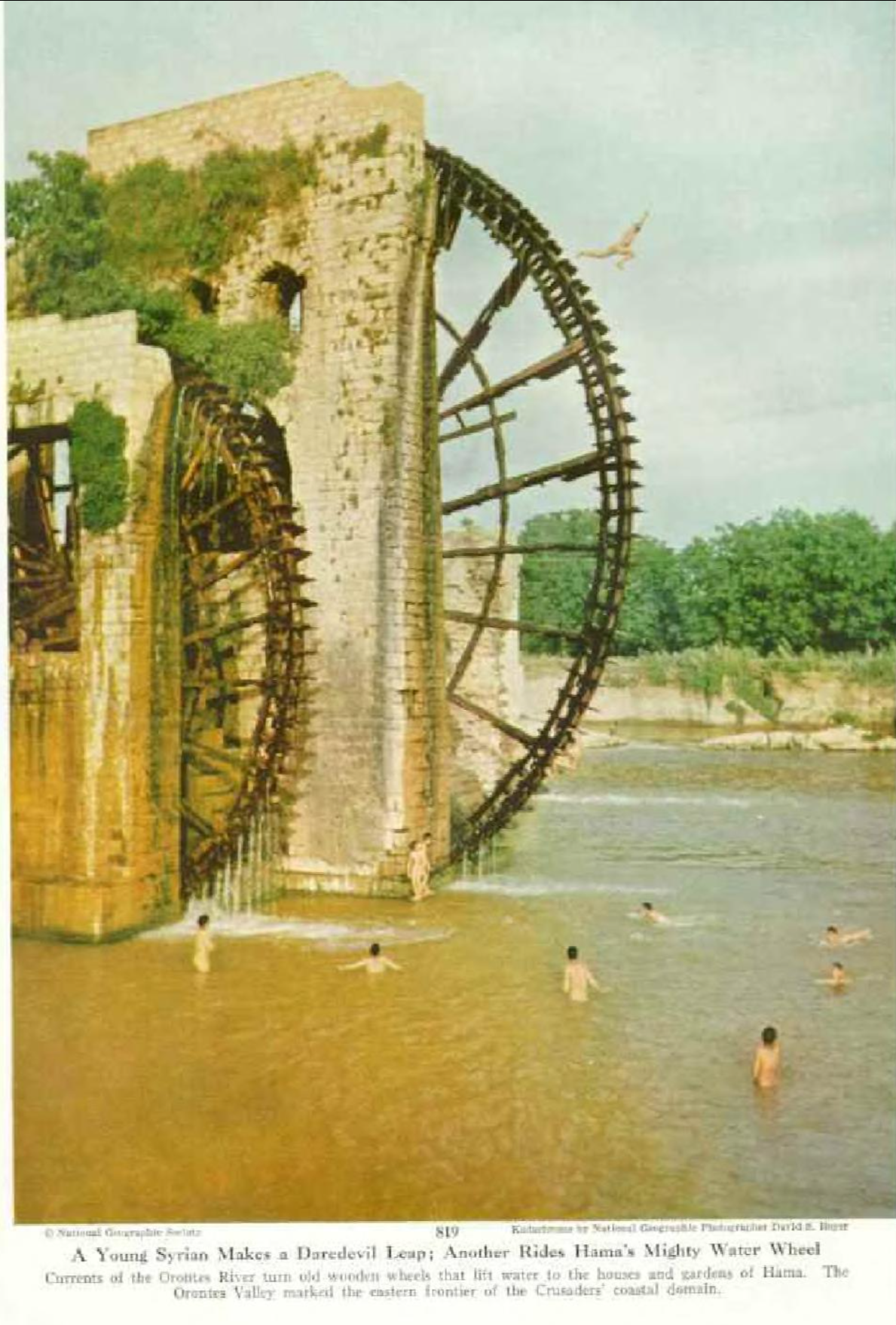

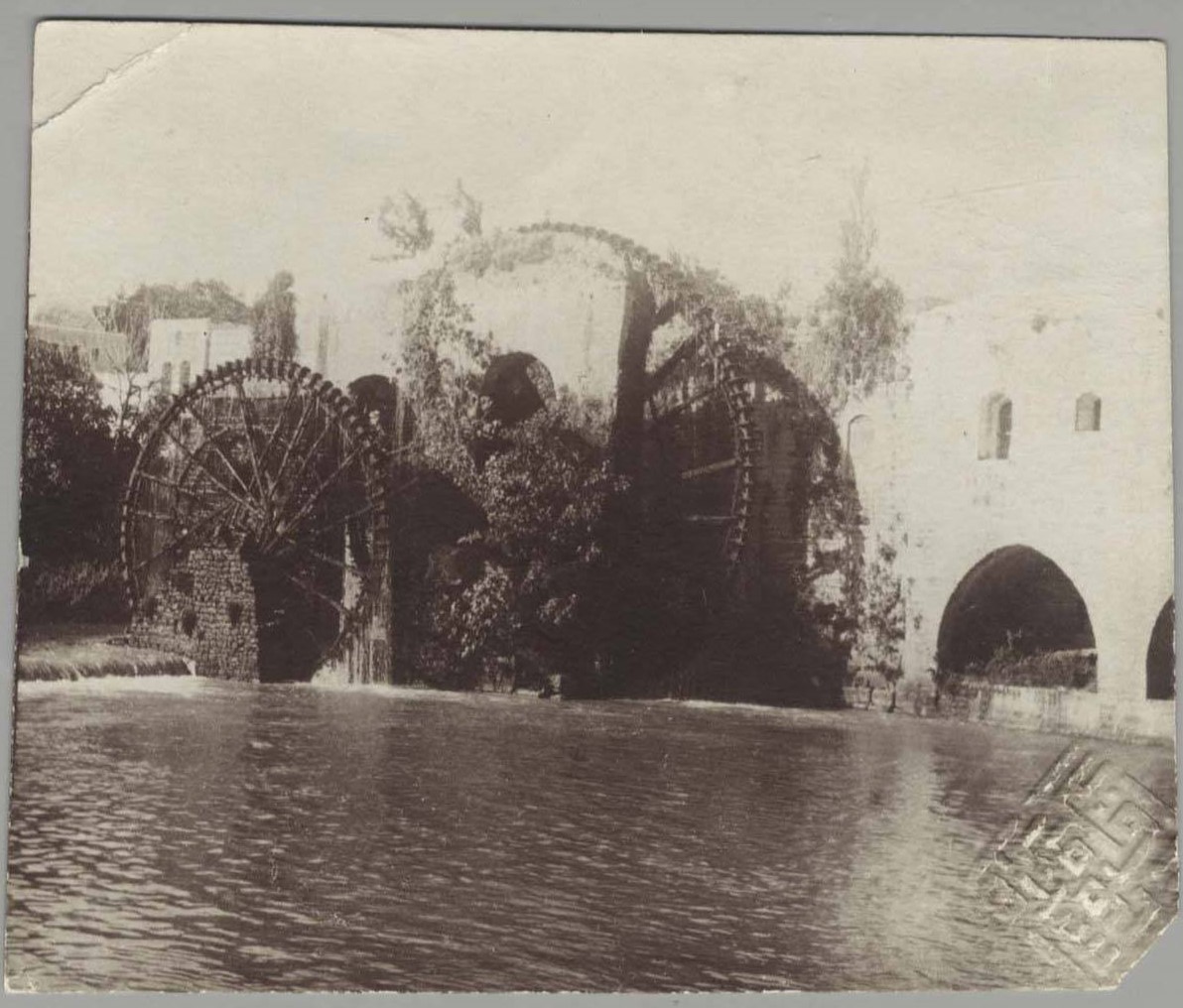

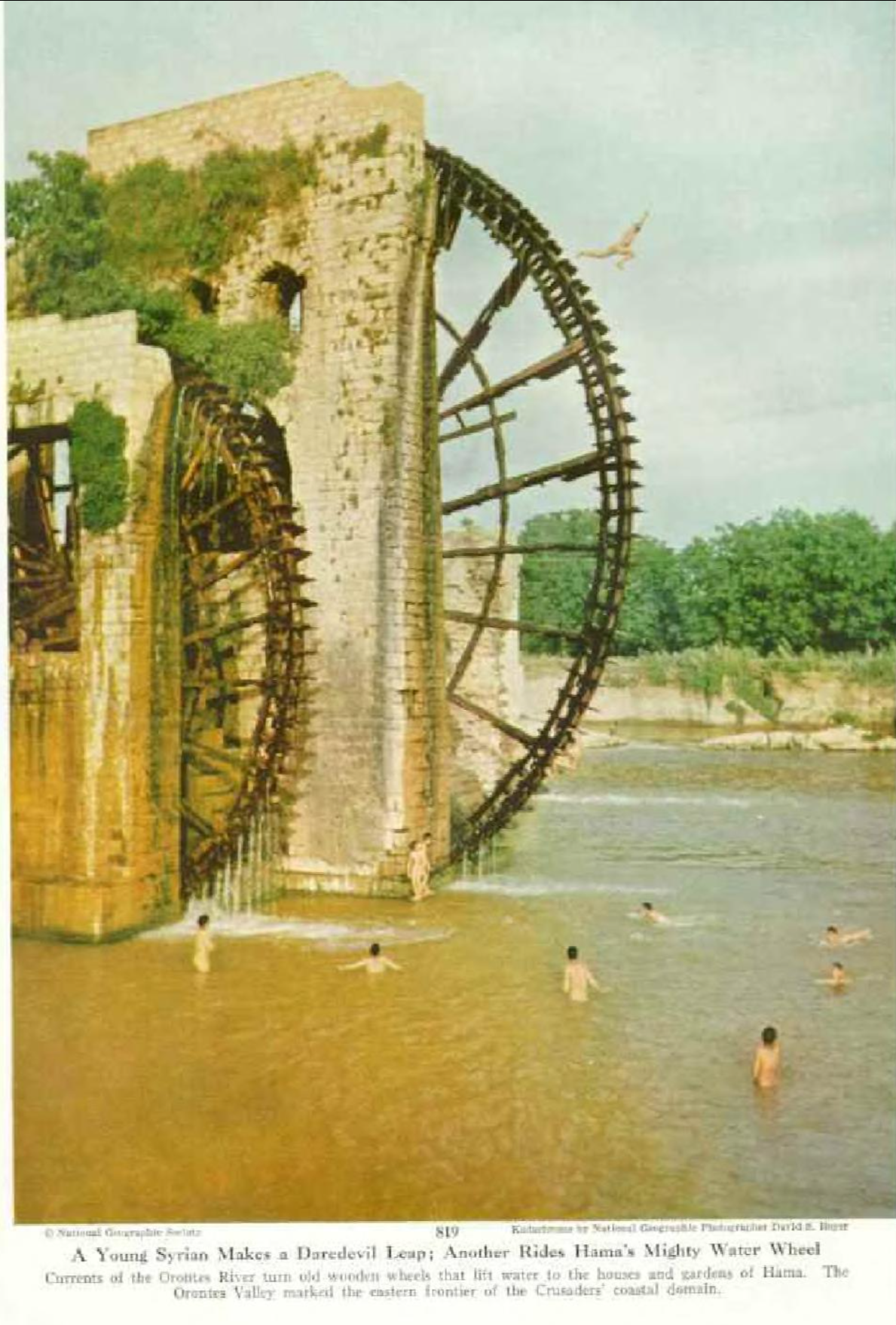

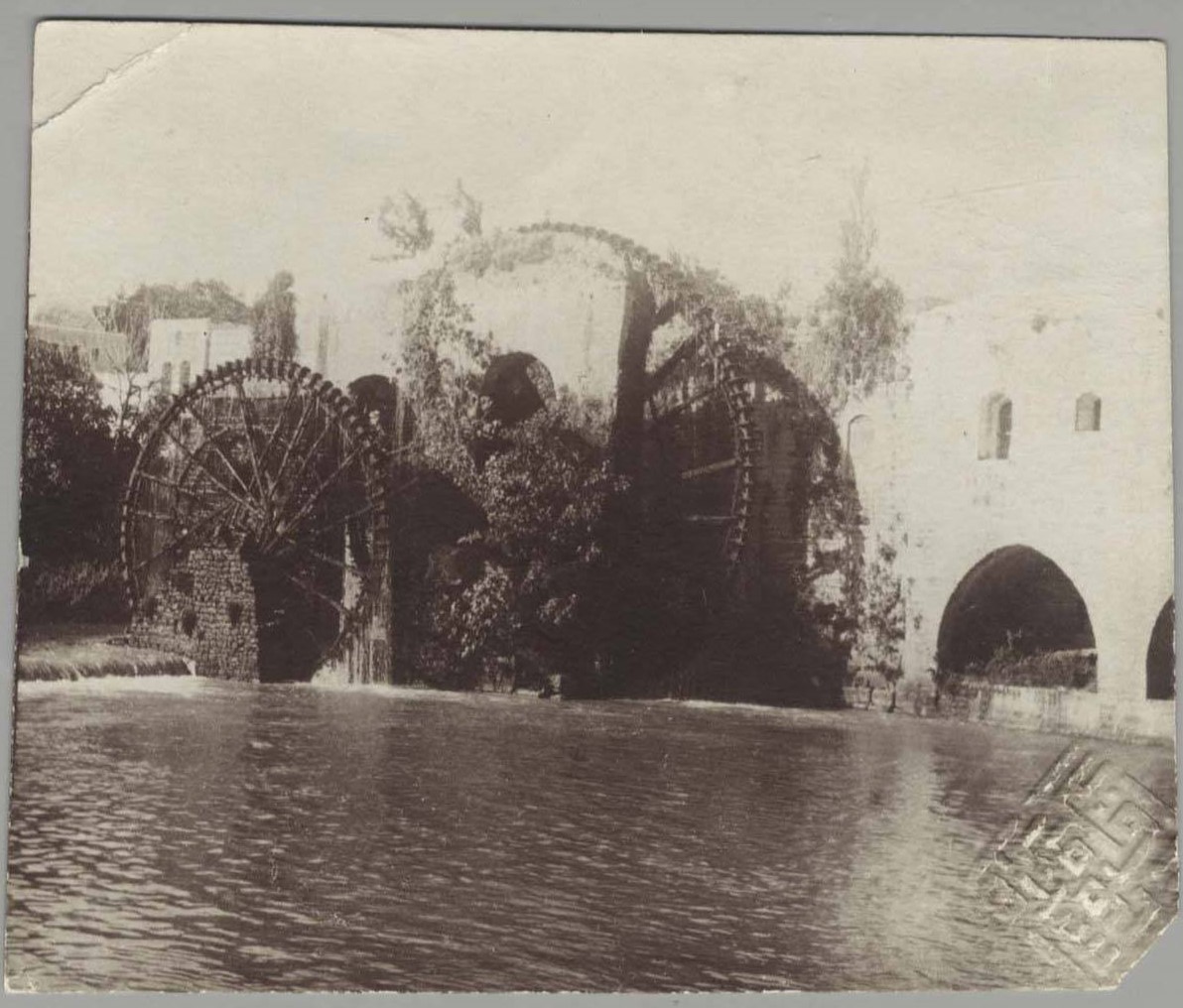

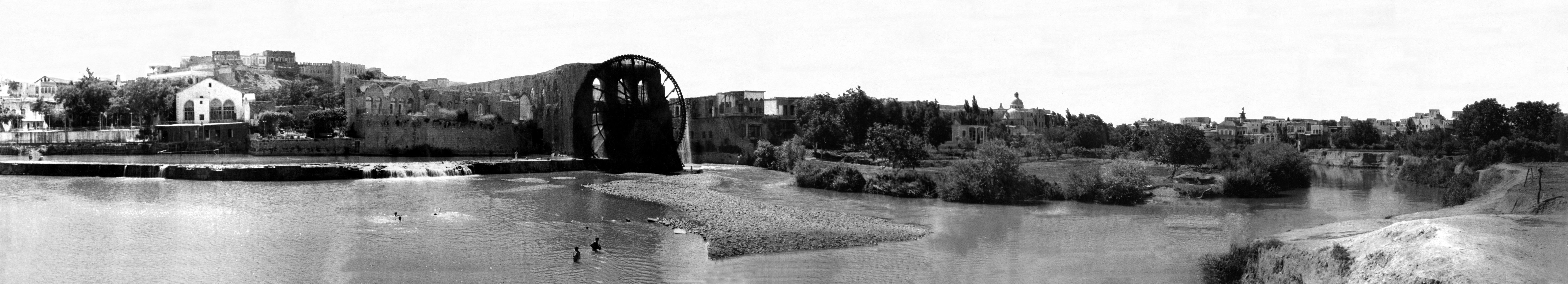

As the heartbeat of Hama’s historical transformation, the norias continue to resonate in the city’s cultural identity. Even today, the drone of the norias echoes through the gardens of Hama. With fourteen of these medieval goliaths still revolving, they no longer carry agony but joy as visitors ride them and leap into the water below (See Fig. 1.3).

The norias of Hama were once an innovative solution for lifting water to drive agriculture. Now, these creaking behemoths have evolved into engineering masterpieces and cultural icons, shaping modern culture through tourism, recreation, and even appearances in video games.

Figure 1.2 . Institut Français Du Proche-Orient, Armée Du Levant. Syria, Hama Governorate, Tell Hama, oblique aerial view, 24 April 1936.

The mound, also called “the fortress” or “the castle,” is located in the heart of Hama. It is 300 m (1,000 feet) wide and 400 m (1,312 feet) long, towering 150 feet above the city. The mound was formed after thousands of years of occupation, which remained contained until the Roman expansion during the Bronze Age (NMOD).

Figure 1.3 . Boyer. Young Syrian Makes a Daredevil Leap; Another Rides Hama’s Might Water Wheel, Dec. 1954.

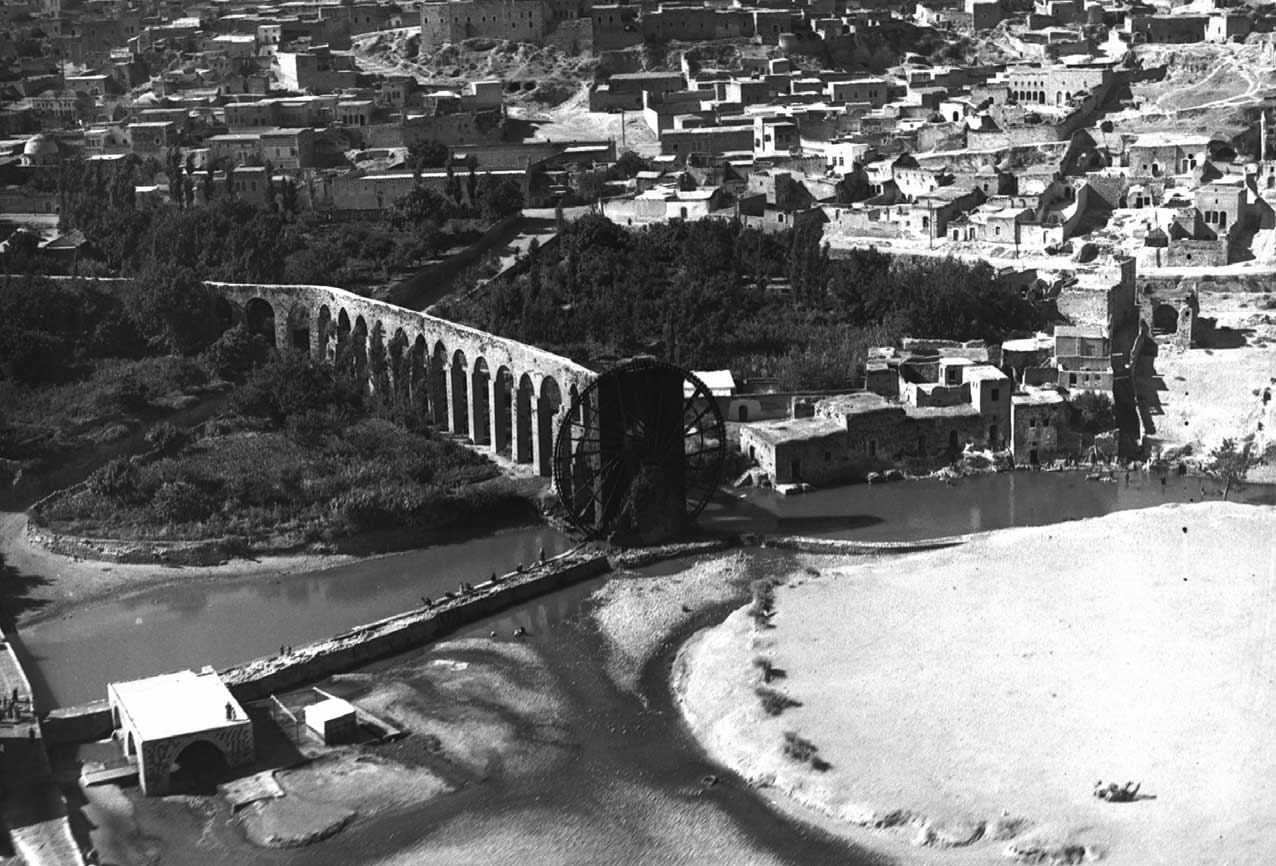

Currents of the Orontes River turn old wooden wheels that lift water to the houses and gardens of Hama. The Orontes Valley marked the eastern frontier of the crusaders’ coastal domain.

THE NORIA

The word "noria" in English means “device for raising water.” It was derived from the Arabic word nurah, which was used to describe water wheels, but the literal translation of nurah is “the wailer” (ASME 4). This is a fitting name for the deep, thundering cries emanating from the wooden structures they are made of. With each rotation, the norias fill their buckets, carrying water up into the stone aqueducts to be transported throughout the city.

Design

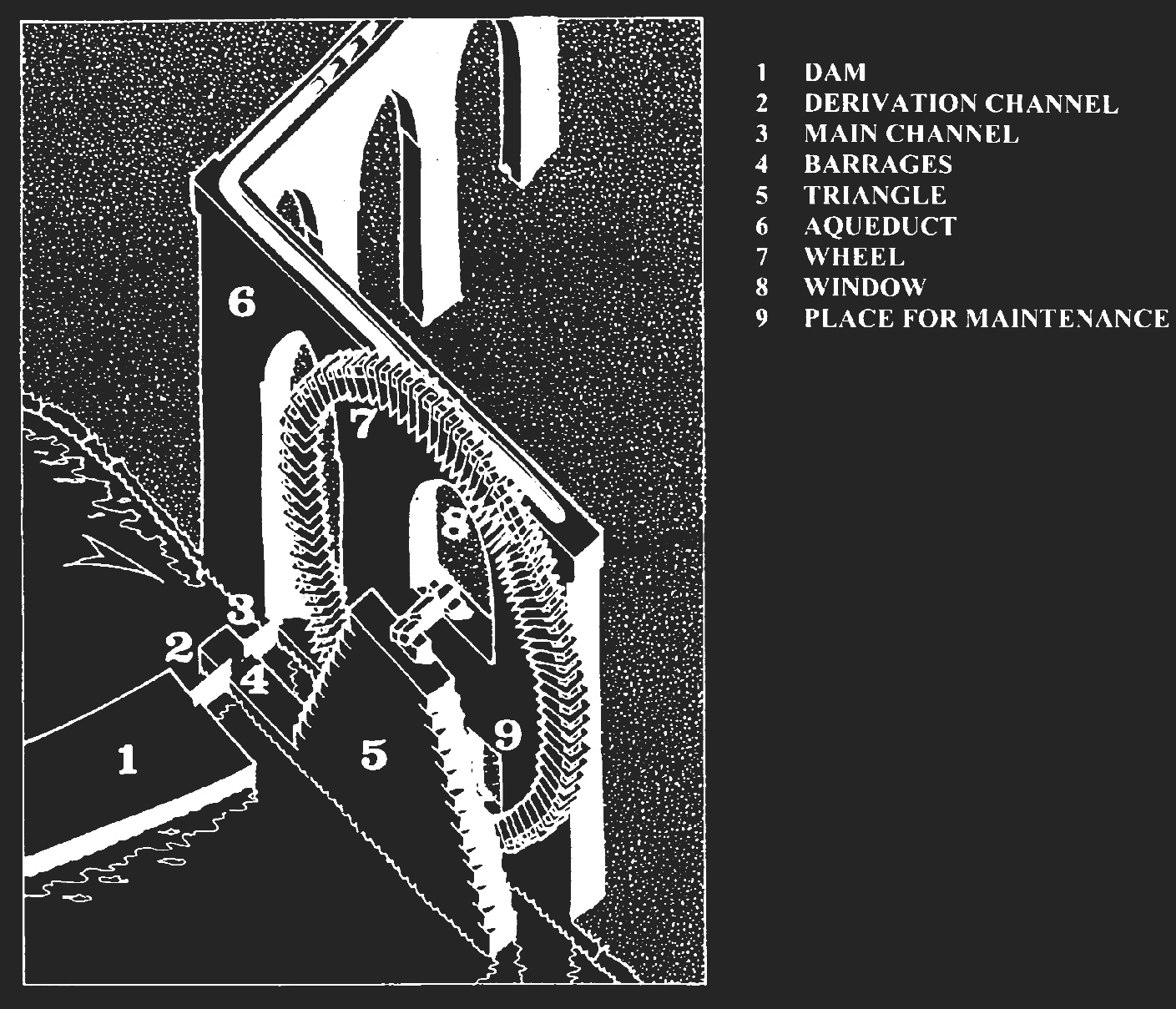

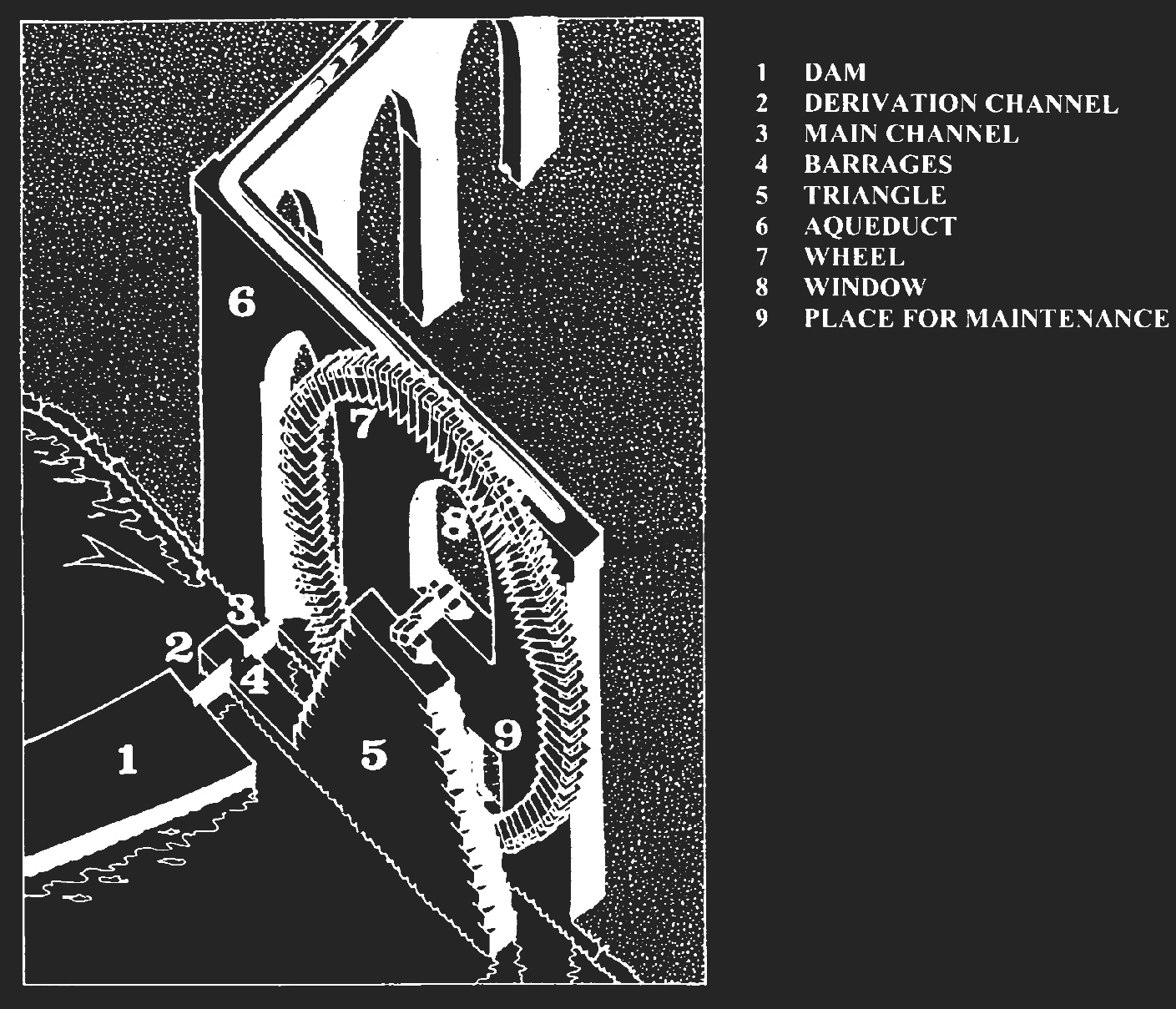

A team of parts working in unison enables the noria to move water. The main components consist of the wheel, dam, and aqueduct. The wheel is the heart of the noria, pumping water with each breath, while the dam and aqueduct form the veins and arteries, supplying and carrying water (see Fig. 2.1).

Figure 2.1 . de Miranda, A. Axonometry of a hydraulic noria. Design and Nature II, edited by M. W. Collins and C. A. Brebbia, vol. 73, 2004, pp. 110.

The Wheel

The wheel is constructed from a large wooden axle, made of hardwoods such as walnut, mulberry, poplar, or apricot, with timbers splaying out from the center hub in an intricate web toward its rim (see Fig. 2.2). The rim is a circular wooden frame with paddles around its perimeter; these paddles are key to harnessing the power of the water as it flows through the main channel (see Fig. 2.3). Between the paddles are enclosed wooden boxes, called sanadiq, with an opening on the outer side to allow water in from the river and dump it into the aqueduct (see Figs. 2.4 and 2.5) (Hafian; de Miranda 107-111).

Figure 2.2 . Hafian, Wa'al. Noria al-Kudhra, al-Dawalik and al-Dasha (Hama, Syria). 2024.

Figure 2.3 . Hafian, Wa'al. Noria al-Kudhra, al-Dawalik and al-Dasha (Hama, Syria). 2024.

At the top of the noria you can see the water pouring from the sanadiq into the collection area of the aqueduct.

Figure 2.4 . Hafian, Wa'al. Noria al-Kudhra, al-Dawalik and al-Dasha (Hama, Syria). 2024.

Figure 2.5 . Hafian, Wa'al. Noria al-Kudhra, al-Dawalik and al-Dasha (Hama, Syria). 2024.

Figure 2.6 . NMOD. The water wheel al-Muhammadiya.

Purpose

“Norias are water wheels, but not all water wheels are norias” (ASME 4). Norias are a type of water wheel used strictly for lifting water, which differentiates them from water wheels designed to grind wheat or power sawmills. The norias of Hama were used for a variety of purposes, such as supplying homes, bathhouses, and irrigating crops.

Noria al-Muhammadiyya supplied water to the al-A’la Mosque, the bathhouse of Hammam al-Dahab, as well as the gardens, houses, and fountains in the area. Although norias are not used directly for milling wheat, traces of mills can still be found near some norias (Hafian). With the ability to move 120,000 liters (32,000 gallons) of water per hour, a single noria could “irrigate no less than 75 hectares” (Hafian) of farmland.

Age

In 1931 CE, Noria al-Muhammadiyya was built by Aydamar Ibn ‘Abd Allah al-Sayhi al-Turki. This noria can be dated thanks to an inscription located on its foundation, as seen in Figure 2.1. The earliest evidence of norias comes from a mosaic dated to 469 CE, found in the ancient city of Apamea, 50 km (31 mi) northwest of Hama, also located on the Orontes River. The mosaic tiles depict norias, as shown in Figures 2.2 and 2.3 (University of Warsaw (UW)).

Stevenson makes a convincing argument that norias were used for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. If true, this would date norias to the Neo-Babylonian era, around 600 BCE (Stevenson 35-55).

Figure 2.7 . ASME. An inscription on the eastern face of the column of the thirteenth arcade of the Noria Al-Muhammadiyya, Dec. 2006. pp. 2.

Translation: This large blessed noria was built in order to take water to the al-A’la mosque during the life of our Honored and Respected Lord, guarantor of the Hamath Kingdom in the year 763.

Figure 2.8 . UW. Discovery of Oldest Representation of a Water Wheel on a Roman Mosaic from Apamea.

The Roman mosaic shows the distinct representation of a noria, with its stone triangle base, dated to Constantinian era (306-337 CE).

Figure 2.9 . Chambrade, et al. Mosaic from Apamea representing a noria, 17 April 2015.

The existence of norias is attested since the Byzantine period (395-636 CE) thanks to a mosaic from Apamea, dated 469 CE.

Noria’s Transform

Hama Grows

The Orontes Valley forms a boundary between the deserts of Syria and the mountains to the west, placing Hama at the center of the wet/dry farming zone. With its fertile terra rossa soil and the Orontes River, Hama was in a prime position for economic growth. The norias ensured a consistent water supply and the irrigation of crops, even during the hostile dry season, making them a matter of life and death (NMOD; Bartl 2; UW).

Figure 3.1 . Waterwheel in Syria, the city of Hama in Syria is famous for its ancient water wheels, or noria.

The Four Noria

In the Early to Late Bronze Age (2400–1200 BCE), continuously occupied settlements were found along the banks of the Orontes. However, during the Iron Age (1200–333 BCE), there was a decline in the number of settlements (Bartl 16–18). Then, during the Hellenistic period (300–50 BCE), new and renewed settlements began to emerge. This correlates with the first evidence of sāqiya and treadwheels (animal- and human-powered waterwheels) dated to 300–10 BCE. The structures of this period were associated with agriculture, transforming the arid landscape into one that could flourish (Wilson 1–30).

During the Roman and Early Byzantine periods (65 BCE–636 CE), the area was free of political strife, creating a time of peace and development, which marked the era of highest settlement density (Bartl 19). In the Roman era, norias came into mainstream use, driving agriculture and, in turn, the economy, which created an enriched and thriving population (Wilson 9; Chambrade).

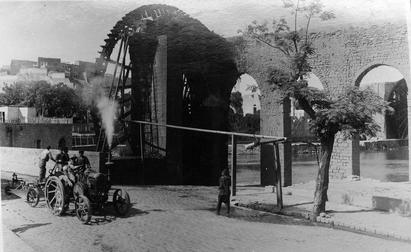

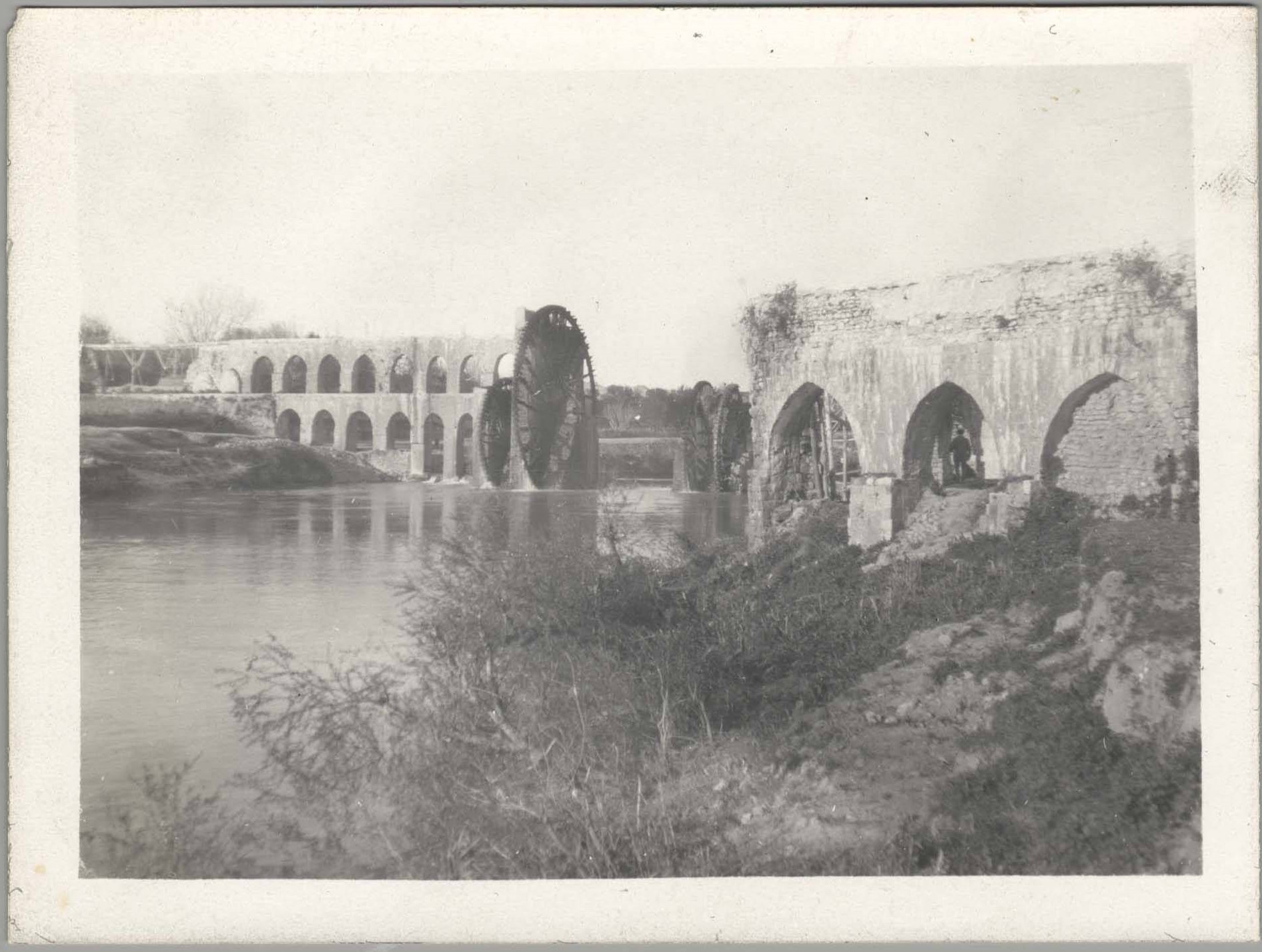

Figure 3.2 . Dick. Hama (Syria): view of water wheels on the Orontes River. 1943.

Innovation

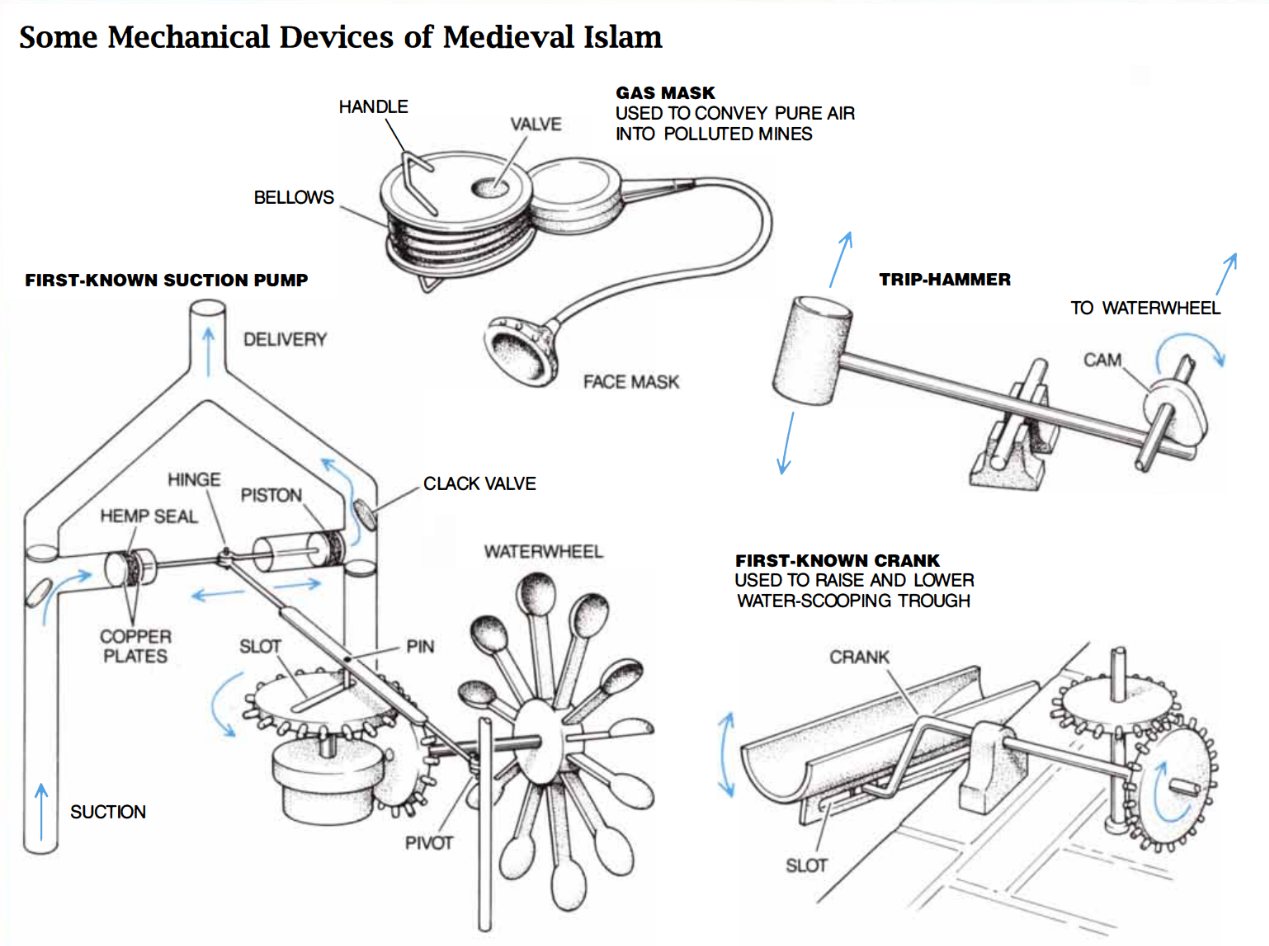

With the noria drawing its power directly from the water, it can move vast amounts of water without relying on animal or human labor. This surplus water could then be used for fountains and technological developments (see Figures 3.3–3.5).

During the medieval period, there was an increase in references to norias in geographical writings, indicating their significance and continuous development (Hafian). As Hama's population grew, norias spread throughout the region, with a total of 90 documented. Of these, 50 were still operational and supplying water in the early 1900s. However, their numbers dwindled due to natural disasters and war, and today, only 14 remain standing (NMOD).

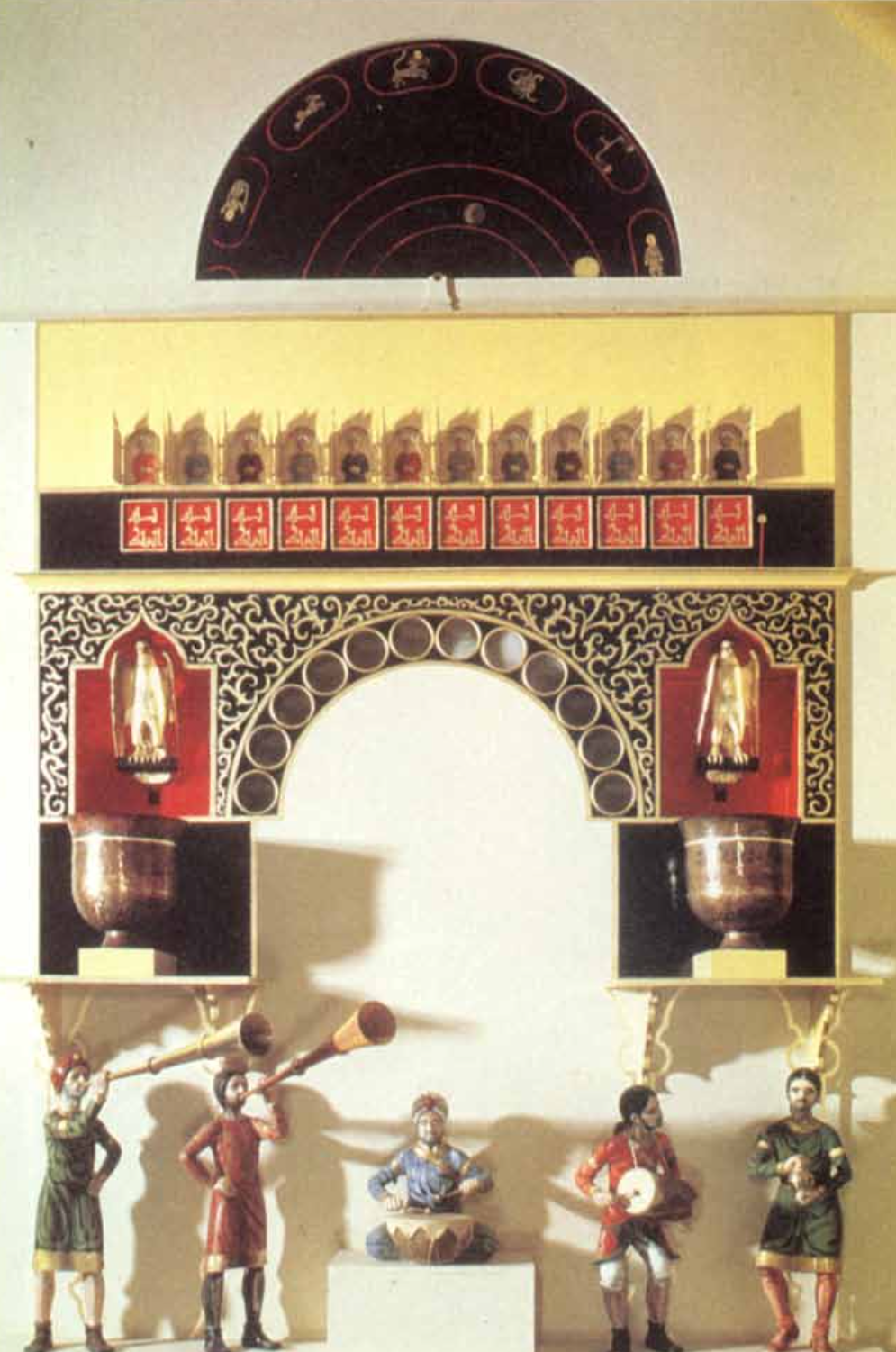

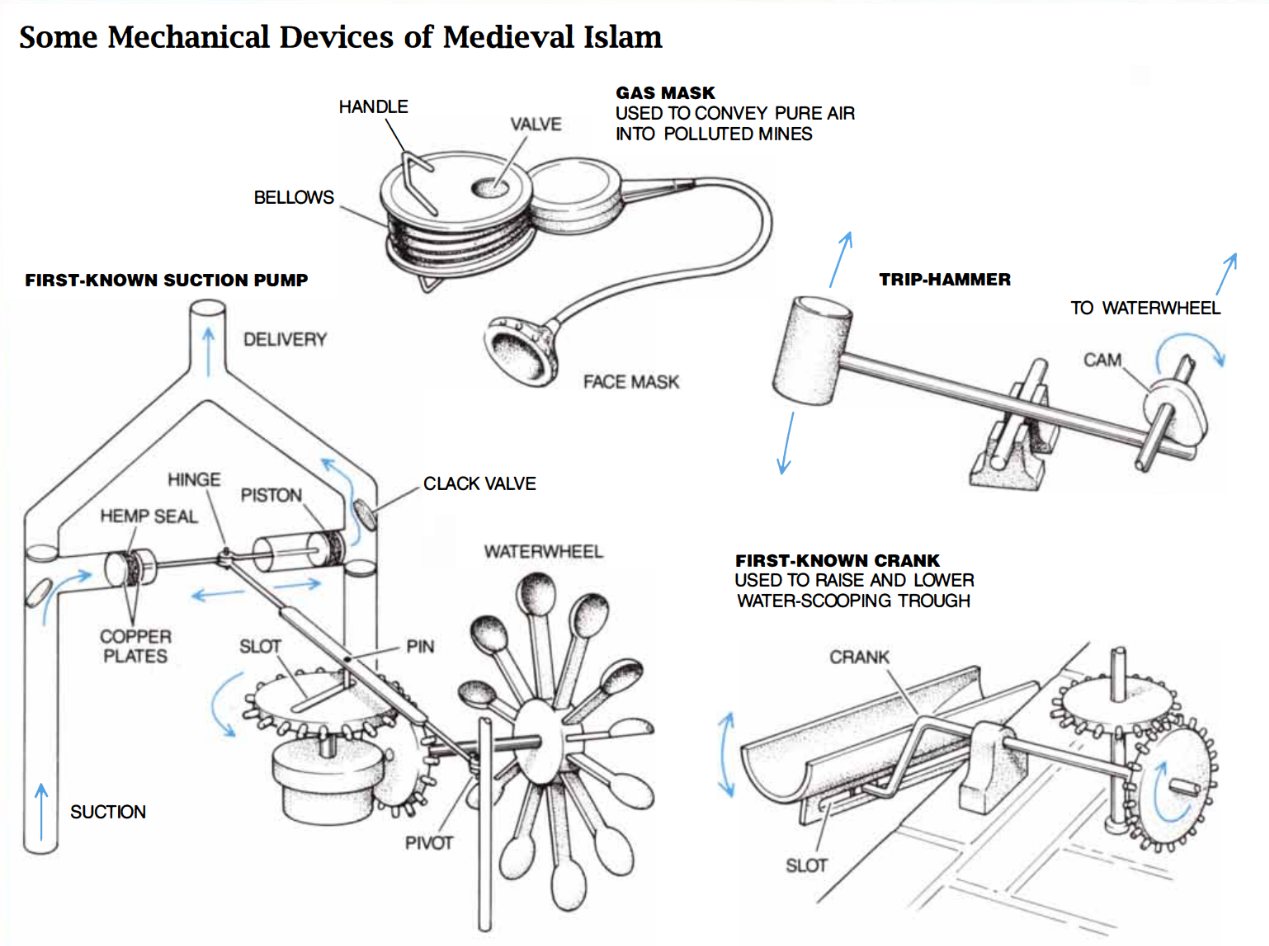

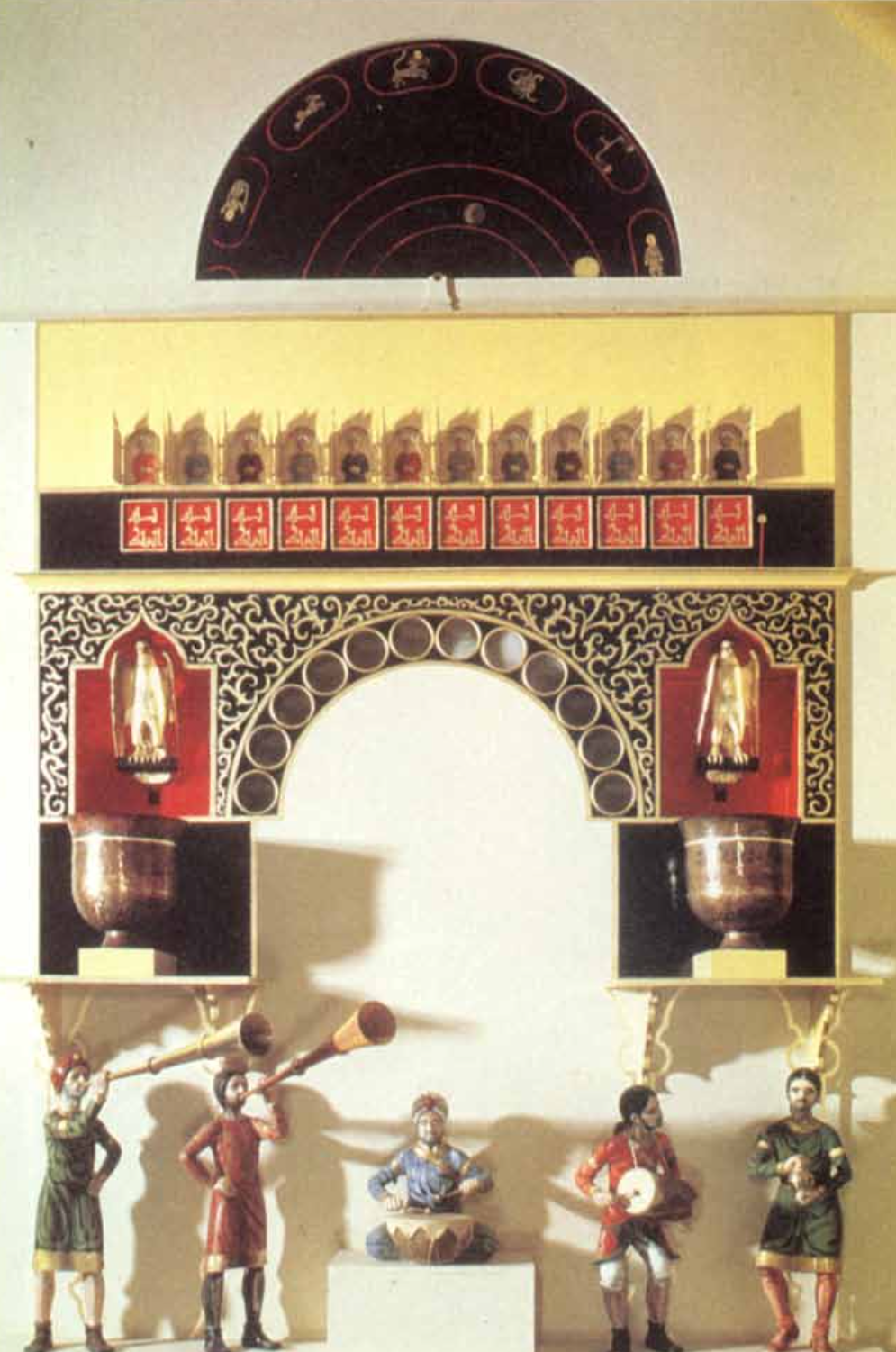

Tinkers found ways to use the excess power generated by norias to develop novel devices, such as the first known suction pump and the water clock. The water clock utilized valves and hydraulic controls to track not only the time of day but also the seasons and the signs of the Zodiac (see Fig. 3.4) (Hill 102–105).

Figure 3.3 . Hafian. Discover Islamic Art: Norias (Nawa’ir) of Hama. 2024,

Figure 3.4 . Hill. Water clock reconstructed according to al-Jazari's specifications, incorporates 'in-line' valves and other hydraulic controls. The clock measures time both by the hour and by the seasonal progression of the signs of the Zodiac. May 1991, pp. 102.

Figure 3.5 . Hill. Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East. May 1991, pp 104.

Culture

With the enormous impact that the norias had on the development of Hama, they have influenced both local and global culture. Known as the "City of Wheels," Hama has become a hub for tourism, while the norias themselves have achieved recognition as engineering landmarks, further inspiring video games and artwork.

Recreation

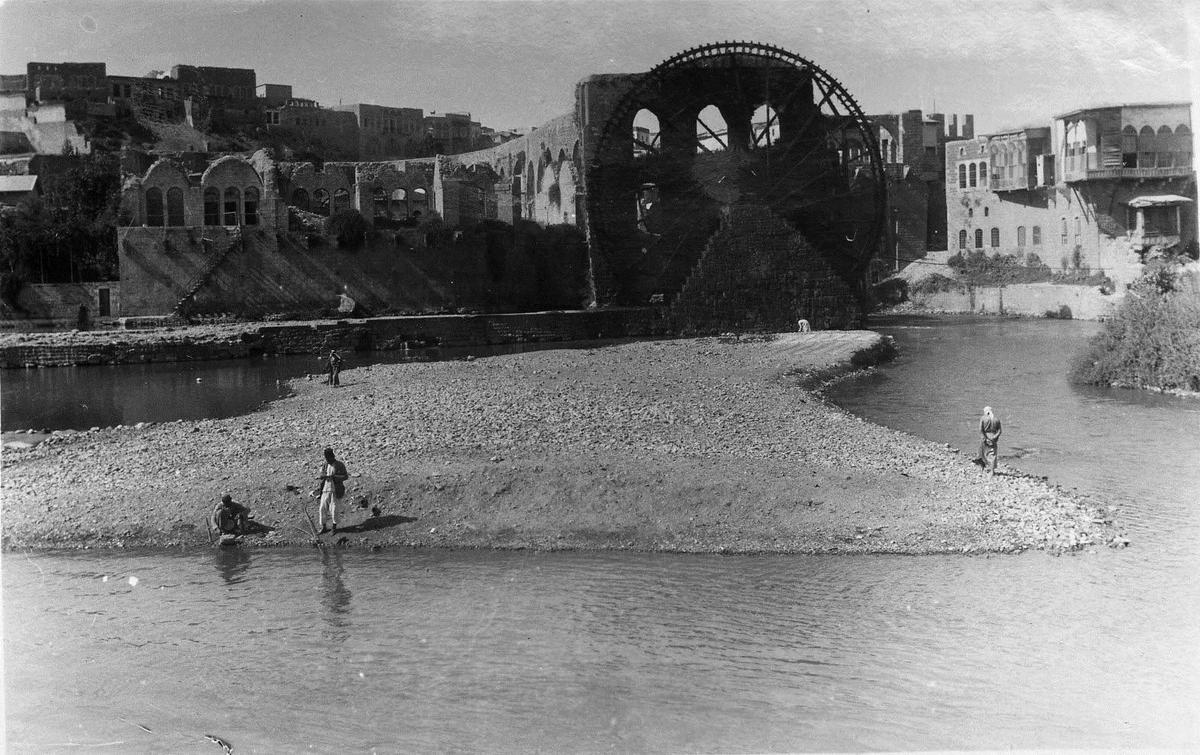

The dams of the noria, forming convenient swimming pools, and the revolving wheel, acting as an elevator, made the noria a source of recreation to cool off during the summer. People rode the noria, using it as a unique diving platform, while the less adventurous waded in the surrounding water, washed clothes, or went fishing (see Figs. 1.3, 4.1, and 4.2).

Figure 4.1 . Dick. Hama (Syria): view of water wheel on the Orontes River, 1943.

The image depicts a mother and daughter in the Orontes River, with a noria in the background.

Figure 4.2 . NMOD. The water wheel al-Mamuriya.

The image depicts five people on an island in the river, with Noria al-Mamuriya in the background.

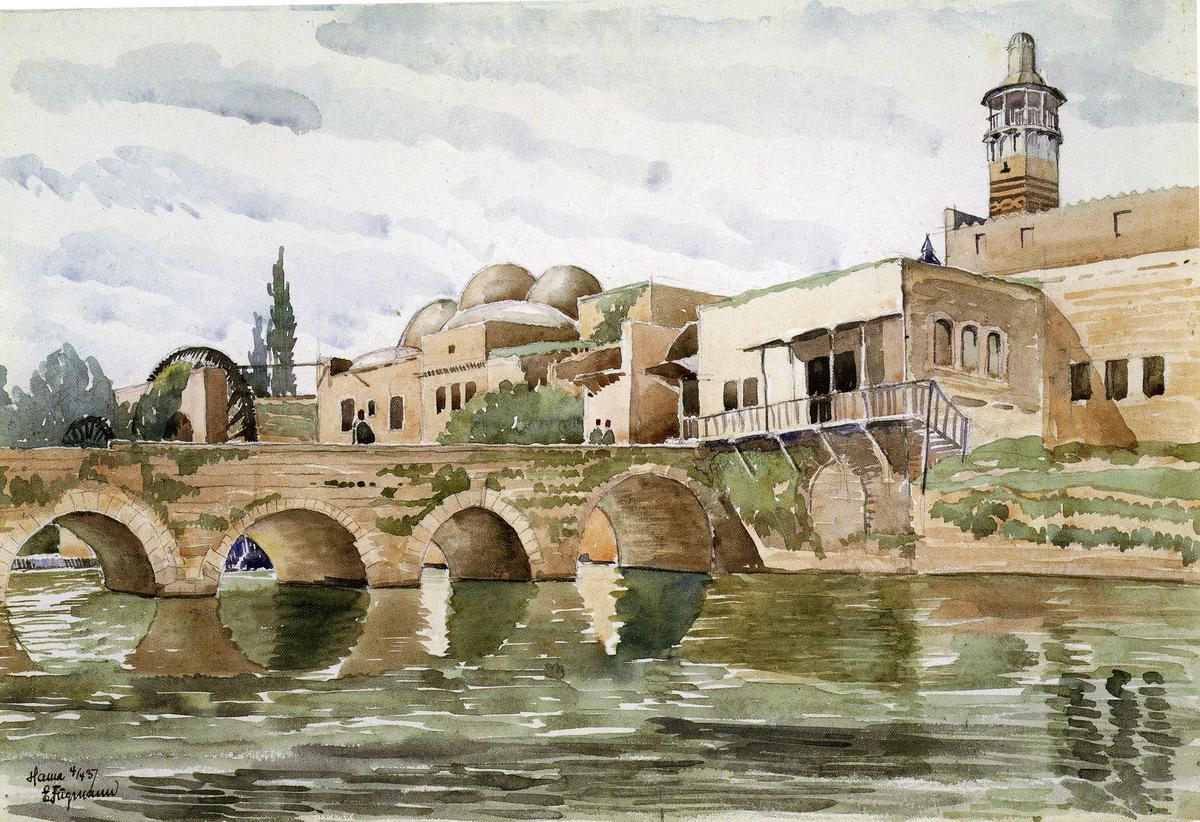

Art

The influence of the water wheels was not only practical but also artistic. While on an expedition to Hama, architect Ejnar Leo Fugmann was inspired by the norias and painted around 100 watercolors of Hama and its water wheels (see Figs. 4.3 and 4.4) (NMOD). The norias have also inspired poets, as seen in Considerations about the Dolab-nama, where Türkan has collected poems inspired by water wheels. I have translated one such poem, shown in Figure 4.5.

Türkan also writes the following passage, highlighting the reputation the norias have established:

The waterwheel has become an indispensable classic for Turkish poets because it turns slowly, making sounds similar to crying. In these poems, the lover identifies himself as a waterwheel. The love and the screams of the lover with the feeling of staying apart from their beloved are similar to the groans heard from far away Dolab-nama also means the verse in question from the language of the water closet with the question, “Expressing the chant of love of Allah.” Moreover, the insufficient definition of the dolab-nama was emphasized (Alvan 443)

The Ode of the Water Wheel

Today, I questioned a water wheel,I asked, "Why do you turn upon this stream?"

"Why is your chest pierced, your eyes full of tears,

What causes you to lament with such reproach?"

"You have no rest, turning day and night,

Pouring blood-stained tears from sorrowful eyes."

"Your straight stature has bent like a bow,

Your groaning has become a melody for the rebab."

"In the morning, your tears flow endlessly,

You do not find a moment’s sleep at night."

"Why do you cry out in anguish and pain,

Is your sorrow beyond measure or account?"

"Your grieving chest has been pierced by groans,

Your sighs have turned hearts into burning embers."

"What news has fate delivered to you,

That your ledger of grief could not fit into books?"

"What cruelty has this tyrannical wheel inflicted on you,

That you’ve fallen into this endless reproach?"

"Your smoke has darkened the blue skies above,

And your sighs have turned the earth into dust below."

I asked about the water wheel’s endless turning,

And as it turned, the wheel gave me its reply.

Figure 4.5 Güzel qtd. In Alvan 470

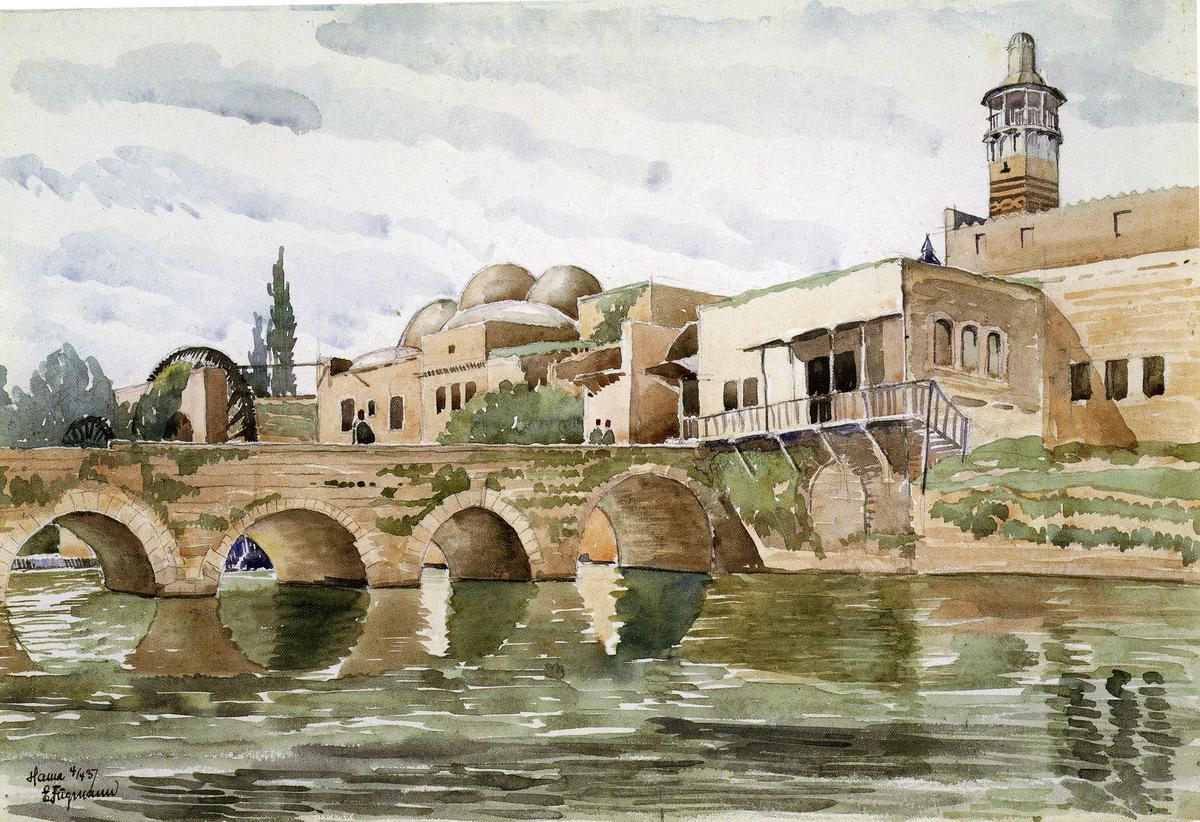

Figure 4.3 . Fugmann. NMOD. Watercolours of Hama in the 1930s, 1935

A view of the Mamuriya water wheel in the Bain al-Hairain quarter. In the distance can be seen the aqueduct of the Jisriya water wheel.

Figure 4.4 . Fugmann. NMOD. Watercolours of Hama in the 1930s, 4 April 1937

The Nuri Mosque, behind the bridge Jisr Bait ash-Shaikh, with the al-Jabiriya and as-Sahiuniya water wheels to the left. The Nuri Mosque was built in 1162, with additions added later. Because there was a school for the study of religion and science attached to the mosque, it played an especially important role in the history of the town. Adjacent to the water wheels is a hospital associated with the mosque.

Tourism

Tourism is also driven by the noria. In 2006, Noria al-Muhammadiyya was listed as an engineering landmark (ASME 10), solidifying its status as a cultural icon of Syria that attracts tourists to admire its beauty. Next to some of the norias are cafes where tourists can relax and enjoy a delicious meal (see Cafe with Noria Table Side and Video of Cafe).

Video Games

The impact of the norias extends even into video games, where their iconic wooden structures captivate creators. With their timeless aesthetic, norias are ideal for world-building games such as Anno 1404 and Kingdoms and Castles, each featuring norias in their gameplay (see Fig. 4.6) (Anno 1404 Wiki; Elreyboro).

Figure 4.5 . Fandom. Anno 1404 Wiki: Noria.

Figure 4.6 . Elreyboro. Kingdoms and Castles: Noria-The water mover. 3 July 2019.

Norias of Hama

- Noria al-Muhammadiyya: The largest and most famous noria in Hama, built in 763 AH (1361 CE), with a diameter of 21 meters (69 feet). It supplied water to the al-A’la Mosque, Hammam al-Dahab, gardens, houses, and fountains.

- Noria al-Bisriyya: Initially called al-Hagibiyya, it has two wheels with different diameters, the larger being 18 meters (59 feet). Restorations occurred in 1977 and 1988.

- Noria al-Utmaniyyatani: Located on the same dam as Noria al-Bisriyya, it features twin wheels, forming the group known as the "Four Norias." Its aqueduct was rebuilt in the mid-20th century.

- Noria al-Gisryya: Previously called al-Yazbakiyya and al-‘Ubaysi, it has a long portion of its aqueduct still existing in the Umm al-Hasan public garden.

- Noria al-Ma’muriyya: The second-largest noria after Muhammadiyya, with a wheel diameter of 21 meters (69 feet). Built by Prince Balbak in 857 H (1453 CE).

- Noria al-’Utmaniyya: A medium-sized noria with a wheel diameter of 11 meters (36 feet), fully restored in 1980.

- Noria al-Ma’ayyadiyya: Formerly called Noria al-Hanqah, it is among a group of three norias and associated with a mill. Its wheel was rebuilt in 1979, with a diameter of 7 meters (23 feet).

- Noria al-Ga’bariyya: Part of a group of three norias near al-‘Azm Palace. Restorations were completed in 1981 and 1983, but its aqueduct collapsed in 1988 and was rebuilt.

- Noria al-Sihyuniyya: A single-wheel noria with a medium diameter of about 10 meters (33 feet). Rebuilt in 1981 and restored in 1988.

- Noria al-Kilaniyya: Built against the now-destroyed Kilani Palace, it has a wheel diameter of 12 meters (39 feet). Restorations occurred in 1981 and 1988.

- Noria al-Hudura: Located north of the Hama citadel, it is part of a group of three norias. It was restored in 1982, 1983, and 1988, with a wheel diameter of 17.5 meters (57 feet).

- Noria al-Dawalik: The aqueduct has disappeared, but the wheel was restored in 1983 and 1988. It operates a mill.

- Noria al-Dahsa: A small noria sharing a dam with others. Its peculiarities include alternating large and small buckets and no inner circle. It was restored in 1988.

- Noria al-Maqsaf: Among the smallest norias, it shares a dam with larger norias and a mill. It was restored in 1984.

Conclusion

The Norias of Hama stand as a testament to human ingenuity and resilience of medieval engineering. From their origins for irrigation and water supply the enormous wooden wheels have transcended into cultural icons and symbols for Hama’s rich history. Their deep groans, once perceived as the cries of laboring machines, now resonate with poetic echoes, bridging ancient utility with modern wonder. Whether depicted in art, celebrated in poetry, or featured in video games, the norias continue to captivate the imagination of those who encounter them. As both historical landmarks and modern attractions, they embody the enduring relationship between humanity and the natural world, reminding us of the enduring power of innovation to transform societies.

Photo Album

Currents of the Orontes River turn old wooden wheels that lift water to the houses and gardens of Hama. The Orontes Valley marked the eastern frontier of the crusaders’ coastal domain.

A view of the Mamuriya water wheel in the Bain al-Hairain quarter. In the distance can be seen the aqueduct of the Jisriya water wheel.

At the top of the noria you can see the water pouring from the sanadiq into the collection area of the aqueduct.

The Nuri Mosque, behind the bridge Jisr Bait ash-Shaikh, with the al-Jabiriya and as-Sahiuniya water wheels to the left. The Nuri Mosque was built in 1162, with additions added later. Because there was a school for the study of religion and science attached to the mosque, it played an especially important role in the history of the town. Adjacent to the water wheels is a hospital associated with the mosque.

The image depicts five people on an island in the river, with Noria al-Mamuriya in the background.

The image depicts a mother and daughter in the Orontes River, with a noria in the background.

The mound, also called “the fortress” or “the castle,” is located in the heart of Hama. It is 300 m (1,000 feet) wide and 400 m (1,312 feet) long, towering 150 feet above the city. The mound was formed after thousands of years of occupation, which remained contained until the Roman expansion during the Bronze Age (NMOD).

Translation: This large blessed noria was built in order to take water to the al-A’la mosque during the life of our Honored and Respected Lord, guarantor of the Hamath Kingdom in the year 763.

The Roman mosaic shows the distinct representation of a noria, with its stone triangle base, dated to Constantinian era (306-337 CE).

The existence of norias is attested since the Byzantine period (395-636 CE) thanks to a mosaic from Apamea, dated 469 CE.

The mound, also called 'the fortress' or 'the castle,' is located in the heart of Hama.It is 300 m wide and 400 m long, towering 150 feet above the city.The mound was formed after thousands of years of occupation...

The Four Noria

Works Cited

Alvan, Türkan. “The Considerations about the Dolab-nama Genre in Classical Turkish Poetry.” Journal of Turkish Language and Literature, vol. 60, no. 2, 2020, pp. 443-476. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.26650/TUDED2020-0031.

American Society of Mechanical Engineers. "Noria al-Muhammadiyya: Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark." ASME, Dec. 2006, https://www.asme.org/wwwasmeorg/media/resourcefiles/aboutasme/who%20we%20are/engineering%20history/landmarks/241-noria-al-muhammadiyya.pdf.

“Anno 1404 Wiki: Noria.” Fandom, https://anno1404.fandom.com/wiki/Noria

“Al Muhammadiya Noria.” Archnet, https://www.archnet.org/sites/21020

Astour, Michael C. “Tunip-Hamath and Its Region: A Contribution to the Historical Geography of Central Syria.” Orientalia, vol. 46, no. 1, 1977, pp. 51–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43074742.

Bartl, Karin, and Michel al-Maqdissi. "Archaeological Survey in the Hama Region 2003–2005." Syria, vol. HS IV, 2016. OpenEdition Journals, 1 Dec. 2018, http://journals.openedition.org/syria/5107.

Boyer, David S. “A Young Syrian Makes a Daredevil Leap; Another Rides Hama’s Might Water Wheel.” Internet Archive, National Geographic, vol. 6, no. 6, Dec. 1954, pp. 819. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/jishankhan_hotmail_1954/1954-12/page/n99/mode/2up.

Chambrade, Marie-Laure and Myriam Saadé-Sbeih. "Les roues hydrauliques du Proche-Orient: Lieux, techniques et usages." ArchéOrient – Le Blog, 17 April 2015, https://archeorient.hypotheses.org/3936.

de Miranda, A. "Aesthetic Tradition and Ancient Technology: A Case Study of the Water-Wheel." Design and Nature II, edited by M. W. Collins and C. A. Brebbia, vol. 73, 2004, pp. 105-114. WitPress, https://www.witpress.com/Secure/elibrary/papers/DN04/DN04011FU.pdf.

Dick, Harris Brisbane. "Hama (Syria): View of water wheel on the Orontes River." The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMOA), 1943, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll11/id/5249.

Dick, Harris Brisbane. "Hama (Syria): View of Water Wheels on the Orontes River." The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMOA), 1943, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll11/id/5243.

Dick, Harris Brisbane. “Hama (Syria): view of water wheels and aquaduct along the Orontes River.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMOA), 1943, https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll11/id/5273.

Elreyboro. “Kingdoms and Castles: Noria-The water mover.” Steam Community, 3 July 2019, https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=1790816488.

Hafian, Wa'al. "Discover Islamic Art: Norias (Nawa’ir) of Hama.” Museum With No Frontiers, 2024, https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monuments;ISL;sy;Mon01;32;en.

Hafian, Wa'al. "Noria al-Kudhra, al-Dawalik and al-Dasha (Hama, Syria)." Museum With No Frontiers, 2024, https://explore.museumwnf.org/themes/t-1/c-sy/l-185/m-966/lan-en.

Hafian, Wa'al. "Noria al-Muhammadiyya(Hama, Syria)." Museum With No Frontiers, 2024, https://explore.museumwnf.org/themes/t-1/c-sy/l-185/m-1197/lan-en.

Hafian, Wa'al. "Noria Ja‘bariyya, Sahuniyya, and Kilaniyya(Hama, Syria)." Museum With No Frontiers, 2024, https://explore.museumwnf.org/themes/t-1/c-sy/l-185/m-1198/lan-en.

Hafian, Wa'al. "Noria Jisriyya and Ma‘muriyya(Hama, Syria)." Museum With No Frontiers, 2024, https://explore.museumwnf.org/themes/t-1/c-sy/l-185/m-1199/lan-en.

Hill, Donald R. “Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East.” Scientific American, vol. 264, no. 5, 1991, pp. 100–05. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24936907.

Institut Français Du Proche-Orient (ifpo), Armée Du Levant. Syria, Hama Governorate, Tell Hama, oblique aerial view. Photography, MEAE - CNRS UMIFRE 6 - USR 3135, Hama, Syria. 24 April 1936. https://hal.science/hal-02443606v1.

Laessøe, Jørgen. “Reflexions on Modern and Ancient Oriental Water Works.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 1953, pp. 5–26. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.2307/1359477.

National Museum of Denmark. "Life in an Ancient Near Eastern Town." NMOD, https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/historical-knowledge-the-world/the-lands-of-the-mediterranean/the-far-east/digital-hama-a-window-on-syrias-past/life-in-an-ancient-near-eastern-town/.

National Museum of Denmark. "The Water Wheels of Hama." NMOD, https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/historical-knowledge-the-world/the-lands-of-the-mediterranean/the-far-east/digital-hama-a-window-on-syrias-past/the-water-wheels-of-hama/.

National Museum of Denmark. "Hama in the 1930s" NMOD, https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/historical-knowledge-the-world/the-lands-of-the-mediterranean/the-far-east/digital-hama-a-window-on-syrias-past/hama-in-the-1930s/.

National Museum of Denmark. "Watercolours of Hama in the 1930s" NMOD, https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/historical-knowledge-the-world/the-lands-of-the-mediterranean/the-far-east/digital-hama-a-window-on-syrias-past/watercolours-of-hama-in-the-1930s/.

Stevenson, D. W. W. “A Proposal for the Irrigation of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.” Iraq, vol. 54, 1992, pp. 35–55. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.2307/4200351.

University of Warsaw (UW). "Discovery of Oldest Representation of a Water Wheel on a Roman Mosaic from Apamea." University of Warsaw, https://en.uw.edu.pl/discovery-of-oldest-representation-of-a-water-wheel-on-a-roman-mosaic-from-apamea/#lightbox[galleryid-27169-1]/0/.

"Waterwheel in Syria." Alternative Energy, edited by K. Lee Lerner, et al., 2nd ed., UXL, 2012. Gale In Context: Science, link.gale.com/apps/doc/PC4205137010/SCIC?u=ncc_paul&sid=ebsco&xid=efe45fc5.

Wilson, Andrew. “Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy.” The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 92, 2002, pp. 1–32. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.2307/3184857.